[ad_1]

Trees are among the most majestic plants in the landscape, and they are essential components of Earth’s ecology. We literally could not survive without these large, beautiful, and life-sustaining botanical wonders. However, unlike herbaceous plants, trees often require a considerable investment of time and money to reach their full potential in cultivated landscapes. Because there are a lot of trees to choose from, we want to get our tree choices right the first time.

To help you narrow down your options, we went to some horticultural experts and asked, “If you could only have one tree, which one would it be?” We recognize that asking them to choose just one favorite plant is a near-impossible request, but they obliged us with some fantastic trees that are right at the top of their lists of favorites. Next time you need a tree, consider adding one of these selections to your list.

‘Avondale’ Chinese redbud is a compact, reliable performer with stunning blooms

Name: Cercis chinensis ‘Avondale’

Zones: 6–9

Size: 10 to 12 feet tall and wide

Conditions: Full sun to partial shade; average, moist, well-drained soil

Native range: China

Cercis is a small genus of roughly 10 species with a worldwide distribution. These trees, commonly known as redbuds, are delightful for many reasons, both aesthetic and practical. They burst out in a gorgeous spring floral display that can range from pale pink to mauve. Like ornamental stone-fruit trees, such as cherry and peach (Prunus spp. and cvs., Zones 5–8), redbuds are smaller trees that bloom before leafing out. Additionally, when the blossom display is finished, they offer attractive foliage that lasts for much of the year. The heart-shaped leaves, similar to those of orchid tree (Bauhinia spp. and cvs., Zones 9–11), can range from a lively green to deep maroon, with many cultivar variations in between.

Western redbud (C. occidentalis, Zones 6–9) is our regional species in Southern California. Like many of our native plants, it has modest water requirements. At The Huntington Botanical Gardens, we also grow a variety of redbud cultivars, such as the beautiful ‘Avondale’ Chinese redbud, which is among my favorites. This smaller option performs reliably and produces stunning blooms that really stand out in the landscape. And like all redbuds, ‘Avondale’ is beautiful, beneficial to wildlife, and easy to manage. It grows well as a companion to woodland understory plants such as ferns and columbines (Aquilegia spp. and cvs., Zones 3–9), as well as with spring bulbs.

The Expert

Nicole Cavender has spent her career dedicated to plant science, conservation, and education. She is currently director of the Botanical Gardens at The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens in San Marino, California.

Nicole’s recommended companions

- Oregon grape (Berberis aquifolium and cvs., Zones 5–8)

- Camas (Camassia spp. and cvs., Zones 4–8)

- Heuchera (Heuchera spp. and cvs., Zones 4–9)

For the ultimate beneficial shade tree, choose white oak

Name: Quercus alba

Zones: 3–9

Size: 50 to 80 feet tall and wide

Conditions: Full sun; moist to dry, well-drained soil

Native range: Eastern North America

An arch without a keystone is destined to collapse; likewise, a garden without a keystone species is ecologically vulnerable. From New England west to Minnesota and south to eastern Texas and northern Florida, white oak is the epitome of a keystone shade tree and is without hesitation my favorite. It’s long-lived, of prominent stature—often wider than tall—and lives to a great age. It grows quite fast when planted in undisturbed, upland conditions, often with two growth spurts a season.

Looking spiffy year-round, white oak’s light gray shaggy trunks stand out in winter, and the emerging foliage in spring shines from silvery to pink before maturing green (photo right). The foliage hosts many beneficial insects that support the web of life. Fall color can be outstanding shades from sienna to purplish red (photo above). Younger trees or the lower branches of older ones often hold their bleached to buff-colored marcescent leaves through winter. The acorn crop is occasionally robust, a feast for more species of wildlife than that provided by any other tree. There are no cultivars of white oak, but choose a tree of local to regional origin for best results.

The Expert

Alan Branhagen is a naturalist, plantsman, and author specializing in botany, butterflies, and birds. His career focus has been on the sustainable nurturing of public gardens and open spaces, and he is currently director of the Natural Land Institute in Rockford, Illinois.

Alan’s recommended companions

- Pagoda dogwood (Cornus alternifolia and cvs., Zones 3–7)

- False Solomon’s seal (Maianthemum racemosum and cvs., Zones 3–8)

- Interrupted fern (Osmunda claytoniana, Zones 3–8)

Seven-son flower is a pollinator favorite for the late-season garden

Name: Heptacodium miconioides

Zones: 5–9

Size: 20 to 25 feet tall and 15 to 20 feet wide

Conditions: Full sun to light shade; moist, well-drained soil

Native range: China

I appreciate seven-son flower for its indispensable contributions to the late-season landscape. Blooming toward the end of summer, this tree is at its peak beauty and fragrance when other plants are fading into the background. Its common name was coined by Arnold Arboretum taxonomist Alfred Rehder to describe its inflorescence: six delightfully perfumed white blossoms borne in whorled 6-inch-long panicles, terminated by a seventh flower. The blooms, which are highly attractive to pollinators, give way to showy, vibrant-red sepals that persist through autumn and somehow exceed the splendor of the inflorescences (photo right).

Seven-son flower exhibits a handsome, open growth habit (photo above), with grayish-brown outer bark that exfoliates to reveal a lighter inner bark, adding winter interest. Grown as a small tree or large shrub, it fits well in small urban settings as well as expansive landscapes. The best flowering occurs when it is sited in full sun and well-drained soil.

The Expert

Tiffany Enzenbacher is a grower and plant scientist. Most recently she worked as the head of plant production at Harvard University’s Arnold Arboretum in Boston.

Tiffany’s recommended companions

- Epimedium (Epimedium spp. and cvs., Zones 3–9)

- Smooth hydrangea (Hydrangea arborescens and cvs., Zones 3–9)

- Foamflower (Tiarella cordifolia and cvs., Zones 3–8)

‘Ivory Silk’ Japanese tree lilac is big on fragrant spring blossoms

Name: Syringa reticulata ‘Ivory Silk’

Zones: 3–7

Size: 20 to 25 feet tall and 15 to 20 feet wide

Conditions: Full sun to partial shade; average, moist, well-drained soil

Native range: Japan

There’s a reason I always look forward to seeing the flower buds on the ‘Ivory Silk’ Japanese tree lilac at Powell Gardens. It means that spring has truly arrived in the Midwest and there will be no more cold snaps or random ice storms. The huge panicles of creamy white blooms can be seen from quite a distance, and the flowers’ sweet fragrance drifts across the gardens.

‘Ivory Silk’ is so loaded with blossoms that a few won’t be missed if you take them for cut-flower arrangements. This small tree is the perfect size for most home gardens, and it also has attractive reddish-brown bark on younger stems. ‘Ivory Silk’ is easy to grow and rarely bothered by pests and diseases. I particularly love the dark centers of heucherella (× Heucherella and cvs., Zones 4–11) leaves combined with the tree’s bark. Snowdance™ Japanese tree lilac (S. reticulata ‘BAILNCE’, Zones 3–7), a notable variety with larger leaves that are a darker shade of green, is another excellent choice to consider.

The Expert

Susan Mertz is the director of horticulture at Powell Gardens in Kingsville, Missouri. She has a passion for plants, putting the right specimen in the right place, and botanical photography.

Susan’s recommended companions

- ‘Serendipity’ allium (Allium ‘Serendipity’, Zones 4–8)

- Summer Wine® Black ninebark (Physocarpus opulifolius ‘SMNPMS’, Zones 3–7)

- Double Play® Candy Corn® spirea (Spiraea japonica* ‘NCSX1’, Zones 4–8)

|

|

|

Riveting Rosie™ magnolia won’t get zapped by surprise early-spring freezes

Name: Magnolia sieboldii × M. insignis ‘Riveting Rosie’

Zones: 6–9

Size: 15 to 20 feet tall and 10 to 12 feet wide

Conditions: Full sun; well-drained, acidic soil

Native range: Hybrid

In 2012, I received a seedling magnolia from Kevin Parris at Spartanburg Community College in South Carolina. Unfortunately, the label was lost and the seedling’s identity in limbo until it flowered in 2013. And what a show it was—with exquisite, goblet-shaped, satiny, iridescent pink, fragrant flowers emerging from upright to arching, egg-shaped buds. The flowers, 4 to 5 inches in diameter when fully open, are composed of six to nine tepals, with the gynoecium (pistils) and stamens pink to deep rose. Each tepal is saturated pink on the outer and inner surfaces, and white at the base. Flowers, scattered throughout the lustrous dark green foliage matrix, open in midspring and continue for several weeks. This late-flowering sequence avoids the traditional early spring freezes that obliterate flowers of saucer magnolia (M. × soulangeana, Zones 4–9) and star magnolia (M. stellata, Zones 4–8) in Zone 8 and lower.

Riveting Rosie™ is an absolute standout. Remarkably, it inherited the evergreen foliage of M. insignis (Zones 7–9) rather than the medium-green deciduous foliage of M. sieboldii (Zones 4–8). In Athens, Georgia, the foliage is evergreen to semi-evergreen, while in Hamden, Connecticut, a sister seedling, ‘Oyama Rose’ (Zones 6–9), is deciduous and flowers reliably. The latter is similar, but the tepals are whiter on the interior and pink on the exterior.

The 10-year-old Riveting Rosie™ tree in my garden is 12 feet high and 8 feet wide. Extrapolating from its parentage, I estimate that the mature landscape size will be 15 to 20 feet tall by 10 to 12 feet wide. This magnolia is heat and drought adaptable once established, making it an excellent tree for small and large gardens alike. Although I have noticed flowers sporadically developing on the current season’s growth, the flower buds predominantly form on the previous season’s growth, so prune it after flowering. This tree is a rarity at nurseries, but it’s worth the effort to find.

The Expert

Michael Dirr, Ph.D., is an award-winning horticulturist, breeder, and author with more than 40 years experience as an educator in the green industry. He spent much of his career as a horticulture professor at the University of Georgia in Athens.

Michael’s recommended companions

- ‘O’Kagami’ Japanese maple (Acer palmatum ‘O’Kagami’, Zones 5–8)

- Baptisia (Baptisia spp. and cvs., Zones 3–9)

- ‘Rachel Jackson’ aster (Symphyotrichum oblongifolium ‘Rachel Jackson’, Zones 3–8)

Native flowering dogwood shines with multiseason interest

Name: Cornus florida and cvs.

Zones: 5–9

Size: 12 to 20 feet tall and 8 to 15 feet wide

Conditions: Full sun to partial shade; moist, well-drained soil

Native range: Eastern North America

Flowering dogwood has often been hailed as the most beautiful native flowering tree in the eastern United States. I heartily agree—it’s a stunner. The flowers themselves are tiny, but each cluster is surrounded by four immense white bracts that array like giant saucers amid the expanding leaves in spring. Each bract is curiously cleft at the tip, which gives the bloom an endearing, slightly disheveled quality. Clusters of raisin-sized, scarlet red berries ripen in fall just as the paired oval leaves turn shades of maroon and silver. The fat-rich fruits are relished by dozens of songbirds, though robins and waxwings claim most of the berries on my trees.

Flowering dogwood is a small tree of the forest understory and edge, with a graceful, layered canopy designed to intercept the maximum sunlight available to it. In the mid-1970s a disease called dogwood anthracnose began affecting the trees, causing branch dieback and even death. Trees toward the northern limit of their range and those in stressed locations such as deep shade and droughty soil are particularly susceptible. ‘Appalachian Spring’ (C. florida ‘Appalachian Spring’, Zones 5–9), a selection found growing wild in Maryland, has proven to be highly resistant and is widely available.

The Expert

Contributing editor William Cullina is the executive director of the University of Pennsylvania’s Morris Arboretum and Gardens in Philadelphia and the author of several books, including the definitive guide Native Trees, Shrubs, and Vines.

William’s recommended companions

- Eastern redbud (Cercis canadensis and cvs., Zones 4–9)

- Virginia bluebells (Mertensia virginica, Zones 3–8)

- Pinxterbloom azalea (Rhododendron periclymenoides, Zones 4–9)

‘Pacific Fire’ vine maple sets the scene aglow in gardens big and small

Name: Acer circinatum ‘Pacific Fire’

Zones: 5–9

Size: 12 to 18 feet tall and 10 to 15 feet wide

Conditions: Full sun to partial shade; fertile, moist, well-drained soil

Native range: Western North America

In the Pacific Northwest, vine maples are commonly used native trees. If you’re looking for something similar to the straight species but with a little more pizzazz and multiseason interest, however, consider ‘Pacific Fire’ vine maple. This selection has the same circular leaf shape and multistemmed branching structure as the straight species, but it’s slower growing and more compact, making it a great choice for urban landscapes. Where it really stands out, though, is its coral-red stems that glow against our gray winter skies. I’ll never forget a client telling me once how a grouping of three that I planted on the front edge of her woodland was her favorite thing to see from her bedroom window.

‘Pacific Fire’ grows best in partial shade. The more sun it gets, the more the leaves take on a bronze hue. In fall, their colors range from golden yellow to burnt orange. ‘Pacific Fire’ is also remarkably adaptive to multiple soil conditions. From a design perspective, it can be used in numerous ways—as a single specimen at a front entry, as a grouping for privacy and screening, or, as I did for my client, as a transition from a more formal garden to the woodland beyond.

The Expert

Courtney Olander, a professional landscape designer, is the owner of Olander Garden Design in Seattle. She has a passion for creating spaces that blend lifestyle and horticulture.

Courtney’s recommended companions

- ‘Jack Frost’ brunnera (Brunnera macrophylla ‘Jack Frost’, Zones 3–8)

- Sunset fern (Dryopteris lepidopoda, Zones 5–9)

- Scarlet Ovation™ California huckleberry (Vaccinium ovatum ‘VacSid1’, Zones 7–9)

|

|

Chinese ironwood serves up striking fall color in locales where it’s hard to come by

Name: Parrotia subaequalis

Zones: 5–9

Size: 25 to 30 feet tall and 10 to 15 feet wide

Conditions: Full sun to partial shade; moist, well-drained, acidic soil

Native range: China

Chinese ironwood should be a rage anywhere in the Gulf South, where fall color is difficult to find. Introduced into culture in North America in 2004 by plantsman Ozzie Johnson, it’s still rarely encountered. What’s unique about this species is that it was found in eastern China, about 3,500 miles away from the natural range of Persian ironwood (P. persica, Zones 4–8), which has been in culture for over 100 years in North America. What sets Chinese ironwood apart from its Persian relative is fall color, which starts off maroon and transitions into fire engine red. It’s marcescent, holding the foliage well into the winter.

Chinese ironwood grows fast and is very easy to propagate from cuttings taken in late spring. It’s been bone hardy in East Texas. In fact, in February 2021 it survived an East Texas all-time record low temperature (below zero) with no damage. It appreciates well-drained, slightly acidic soil, and with age it produces attractive exfoliating bark. I suspect that at full maturity it will top out at a manageable 30 feet tall and half as wide.

The Expert

David Creech, Ph.D., is a retired professor of horticulture and the current director of Stephen F. Austin State University Gardens in Nacogdoches, Texas. He received the Outstanding International Horticulturist Award from the American Society for Horticultural Science in 2022.

David’s recommended companions

- Clethra (Clethra alnifolia and cvs., Zones 3–9)

- ‘Florida Sunshine’ anise (Illicium parviflorum ‘Florida Sunshine’, Zones 6–9)

- Fluffy® western arborvitae (Thuja plicata ‘SMNTPGF’, Zones 5–8)

|

|

|

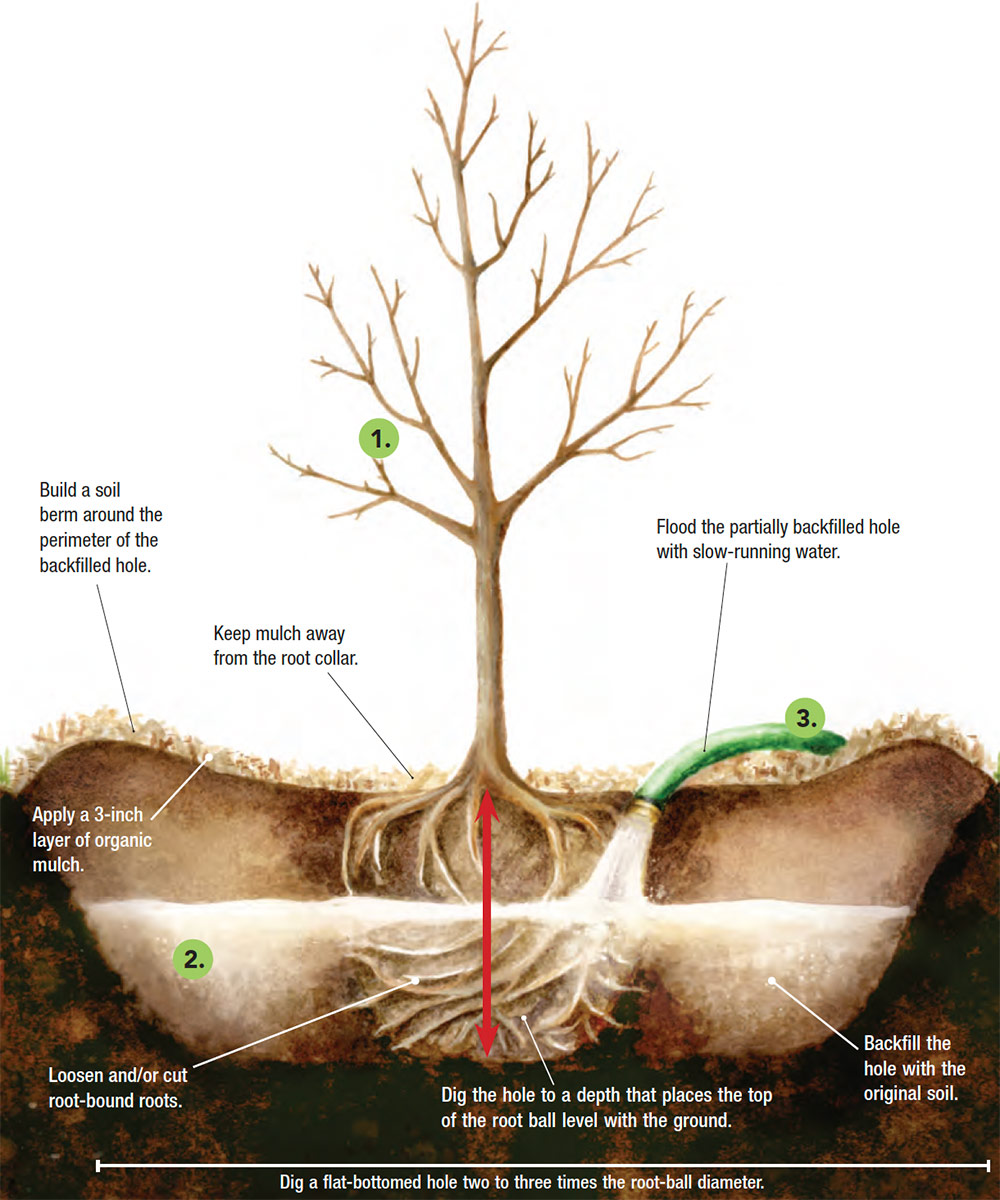

How to plant and care for a tree

Planting a tree is a big investment. Besides choosing the right one for your site conditions and space (trees need a lot of room to grow), how you plant and care for it also matters. Before sinking your shovel into the ground, make sure you are planting your tree at the right time of year and following these basic planting and care strategies.

1. Choose the right time

While summer is a beautiful time of year to be outdoors, it’s the absolute worst time to plant trees. The heat and reduced moisture are big stressors for plants, especially new trees with sizable root and structural systems that need to become established. The best time to plant a tree is in spring. Fall is acceptable too, but absolutely avoid planting in summer.

2. Dig a proper hole

The size and depth of your tree-planting hole matters greatly. Roots benefit from large holes where they can spread easily and become established. However, don’t go too deep or you’ll bury the tree’s root collar, which will reduce the plant’s vigor and might lead to death. The rule of thumb is to dig your hole two to three times wider than the tree’s root ball. The depth should be no more than the height of the root ball.

3. Wet well and often

Trees generally need 1 to 3 inches of water per week throughout the year, but regular moisture is especially important during establishment, hot spells, and dry periods (even in winter). The best way to water a tree is slowly and deeply. Building a temporary soil berm at the perimeter of the backfilled hole helps to prevent runoff and allows water to soak in slowly during establishment. A 3-inch-deep layer of organic mulch also helps to retain soil moisture.

Sources

[ad_2]